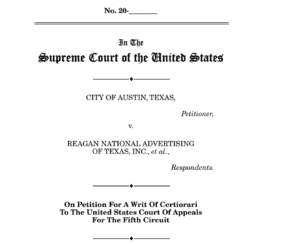

Lots of parties have filed briefs in the Supreme Court’s review of the Austin v Reagan case. Austin wants the Supreme Court to throw out an Appeals Court ruling invalidating Austin’s sign code because it had one set of rules for on-premise digital signs and another set for off premise digital signs. Here’s who’s saying what.

Lots of parties have filed briefs in the Supreme Court’s review of the Austin v Reagan case. Austin wants the Supreme Court to throw out an Appeals Court ruling invalidating Austin’s sign code because it had one set of rules for on-premise digital signs and another set for off premise digital signs. Here’s who’s saying what.

“This case concerns the constitutionality of a municipal sign ordinance that distinguishes between signs connected to the activities conducted on-site and signs that lack such a connection. The United States has a substantial interest in the resolution of issues concerning the constitutional limits on sign regulation. The Department of Transportation, for example, implements the Highway Beautification Act of 1965…which encourages States to limit off-premises signs along certain major highways in the interest of promoting highway safety and preserving natural beauty. Although the ordinance at issue here differs from the Highway Beautification Act, the analysis that the Court adopts in this case may have ramifications for that Act, as well as other federal regulations…The judgment of the court of appeals should be reversed or, in the alternative, vacated and remanded for further proceedings.”

“Since this Court decided Reed, which some courts dubbed a “sea change” while others downplayed its impact (further compounding the confusion for local government attorneys), the decision has resulted in a staggering onslaught of lawsuits against local governments. Litigants are using Reed to invalidate everything from sign codes and panhandling ordinances to wage equity laws and robo-call regulations. In the meantime, thousands of local governments have sought to follow Justice Alito’s guideposts in his concurrence in Reed, which, consistent with Metromedia, allows for distinctions between on/off premises signs. The constitutionality of those distinctions is now uncertain. This Court’s intervention is needed to provide a clear and uniform rule for local governments that seek to balance First Amendment principles with the health, safety, and welfare of their citizenry.”

“Here the court has before it an opportunity to provide much-needed clarity…The planning profession stands ready and able to advance local communities” interests in ensuring that they have safe functional, prosperous and beautiful neighborhoods. Reversing the lower court’s decision which undermines nearly the entire body of existing state and local regulations, is the most direct means of advancing these interests…..”

“At least thirty states and thousands of municipal governments have long treated off-premises billboards differently than on-premises signs, out of legitimate concerns regarding public safety and local aesthetics. Numerous courts, including this Court in 1981, have recognized that distinctions based on billboards’ off-premises locations alone are content neutral. The location of a billboard is not the message of the billboard. Were this Court to hold otherwise in this case, local governments would either face challenges to their off-premises rules under strict scrutiny, or they would have to revamp their sign ordinances once again, a costly and time-consuming process. The main problem with the decision below is its “need to read” test, which posits that if a local official “must read” a sign to determine where it fits in the town’s regulatory framework, then the applicable rule is somehow content-based…The “need to read” test is too onerous, because it could literally be applied to every sign ordinance, obliterating the concepts of content-neutral and concept-based and making all sign rules subject to strict scrutiny review. “Need to read” is also an unworkable test. It is unclear when signs must be read, and the test could be logically applied to subject other reasonable regulations such as noise ordinances to strict scrutiny review. Instead of the “need to read” test, this Court should reaffirm that content-based rules involve a billboard’s topic, idea, or message—not its location. A cursory examination of content-neutral aspects of a sign, such as its lighting, moving parts, or location, is not a content-based inquiry.”

“The on/off-premise distinction has been used for more than a century, most importantly in the Federal Highway Beautification Act of 1965. Millions of businesses and communities have developed in reliance on this basic principle of land use law. This Court has upheld the distinction at least ten times. Two circuits have now held the distinction violates the First Amendment under this Court’s decision in Reed. Three went the other way. Sign owners and communities across the country now face profound uncertainty and protracted, expensive disruption due to this split. We strongly support the petition for writ of certiorari.”

“Outdoor advertising signs have long been regulated through codes that distinguish between their on- or off-premise character. The distinction, endorsed by the Court in Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego, guides much of all sign regulation today and is grounded in the reality that some advertising signs serve fundamentally different purposes that can be wholly related or unrelated to their particular location and land use. This Court’s decision in Reed v. Gilbert did not change the nature of traditional sign regulation grounded in the on-/off-premise distinction and its proper classification as content neutral. The Sign Code in the City of Austin, like the codes in many cities, utilizes the on-/off-premise distinction for certain regulatory purposes and designates certain off-premise signs as nonconforming uses that are not permitted to be modified in ways that expand their degree of nonconformity. The denial of a permit application for a substantial modification of an off-premise nonconforming use that relies on applicable onpremise criteria is not a content-based decision.”

The Columbia University Knight First Amendment Institute

“Amici respectfully suggest that this Court should adopt a more nuanced test of whether a law is content-based and thus warrants strict scrutiny— one that distinguishes between laws that threaten the harms that the presumption against content based lawmaking is intended to address, and laws that do not..Even if the Court declines to revisit Reed’s basic framework, it should, at the very least, clarify that Reed does not mandate strict scrutiny of every law that requires a government official to look at the content of speech. It should make clear, instead, that Reed subjects to strict scrutiny only laws that draw distinctions based on viewpoint or subject matter. Although clarifying Reed’s meaning in this way would not solve every problem the decision has created, it would help realign the content discrimination inquiry more closely with the purposes it seeks to serve and provide needed guidance to the lower federal and state courts. Applying either approach to this case leads to the conclusion that the distinction between on-premises and off-premises signs is not content-based and therefore should not be subject to the presumption of unconstitutionality. The law at issue in this case should instead be subject to intermediate scrutiny.”

International Sign Association

“Respondents invite this Court to upend the workable and well-established on-premises/off-premises distinction by adopting the Fifth Circuit’s sweeping interpretation of content neutrality. But such a paradigm shift would have disruptive consequences for the sign industry and its customers by creating ongoing regulatory uncertainty, imposing serious economic burdens, and chilling protected speech. In addition, the Fifth Circuit’s conclusion rests on an incorrect premise that is contrary to the record and defies the realities of regulatory enforcement: that to ascertain whether a sign is off-premises one “must read the sign.”…Instead of adopting the Fifth Circuit’s overreaching approach, the Court should use this case to clarify that on-premises/off-premises distinctions remain a reasonable content-neutral manner of regulating signs. The Court should uphold the City of Austin’s regulations as constitutional.”

Land Developers, Chambers of Commerce and Scenic America

“The lower court gave zero weight to property rights. While land use restrictions can be burdensome and violate due process, striking down off-premise restrictions would impose enormous costs on landowners and developers. Off-premise restrictions work.”

[wpforms id=”9787″]

Paid Advertisement