The Texas Court of Appeals, for the 14th District in Houston, issued its opinion on May 12, 2022 in Lamar vs Texas Department of Transportation, holding that TxDOT has sovereign immunity against Lamar’s claims that it’s “officials interpreted the rules incorrectly when more than four years after Lamar last paid for its annual permits TxDOT officials determined the annual permits expired without the thirty day renewal notice or late renewal notice.” By way of background, in 2016 TxDOT sent Lamar orders to remove three signs on the grounds the permits had expired due to Lamar’s failure to renew them since 2011. Lamar, in turn, responded that it had never received the required renewal or late notices from TxDOT, and it filed suit against the responsible TxDOT officials for acting ultra vires, or outside their authority, in ordering the signs to be removed without the required renewal and late notices. TxDOT filed a motion to dismiss for want to jurisdiction, claiming Lamar’s suit was barred by sovereign immunity. The Trial Court agreed and dismissed the case, and the Appellate Court affirmed unanimously.

In so ruling, the Court of Appeals first explained the exception to the general rule that sovereign immunity will bar and deprive the courts of jurisdiction in suits against governmental entities: “The illegal or unauthorized acts of a state official are not considered acts of the State and, therefore, an action against a State official complaining that the official acted without legal authority or failed to perform a purely ministerial act is permitted under the ultra vires exception to sovereign immunity. The basic justification for the ultra virusexception to sovereign immunity is that ultra virus acts-or those without authority-should not be considered acts of the state at all. Consequently, ultra virus suites do not attempt to exert control over the state; instead, they attempt to reassert the control of the state over one or more of its agents.” In this case, for example, Lamar argued that, since TxDOT’s rules required its officials to send renewal and late notices before permits could be considered expired and signs ordered removed, the official’s alleged failure to do so fell under the ultra virus exception and jurisdiction should be sustained.

The Trial and Appellate Courts, however, disagreed with Lamar. The Court of Appeals clarified “in a case such as this, to act ultra virus based on the interpretation and application of the law, TxDOT’s officials would have to act ‘without reference to or in conflict with the constraints of the law authorizing [them] to act.’ Under these circumstances, a mistake by an official in granting or denying a permit, or a mistake in interpreting its own rules does not mean that the agency officials are acting without authority in implementing that interpretation.” It went on to emphasize that “it is not an ultra virus act for officials to make mistakes or to make erroneous decisions while staying within their authority. Nor does a failure to provide notice or otherwise comply with procedures constitute an ultra virus act where officials are not acting wholly outside their authority.” The Appellate Court, therefore, affirmed the dismissal of Lamar’s claims under sovereign immunity, concluding “though TxDOT rules provide for notice of sign permit expiration for license holders at specified times before and after the expiration of a permit, the failure to provide that notice alone does not constitute an act wholly outside their authority or a failure to perform a statutorily imposed ministerial duty.”

While the decision is unfavorable for Lamar in particular and the out of home industry in general, the Lamar vs TxDOT case nevertheless leaves unanswered the question of whether the courts would still dismiss Lamar’s claims if they were asserted as counterclaims in a lawsuit initiated by TxDOT. Specifically, the usual practice of TxDOT and other departments of transportation when a sign owner refuses to comply with their orders to remove signs due to expired permits or other rules violations is to sue the sign owner. In such suits, the department argues it ought to be granted an injunction or similar court order for the removal of the sign as a result of the rules violations. Having commenced the litigation and invoked the court’s jurisdiction, the department would then be hard pressed to argue the case should be dismissed on sovereign immunity grounds after the sign owner counterclaimed under the ultra virus doctrine. In fact, it might not be too late for Lamar to test this theory, since its complaints were dismissed on procedural grounds rather than on their merits. By continuing to refuse to remove its signs, Lamar might then be able to reassert those complaints by way of a counterclaim in an inevitable lawsuit brought by TxDOT seeking a judicial order for the removal of the signs.

Stay tuned for further updates.

[wpforms id=”9787″]

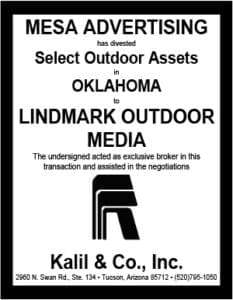

Paid Advertisement

Excellent article.

State officials have two types of duties, ministerial and discretionary. A discretionary duty gives the official room to interpret facts and regulations. A good example: deciding if an application for a permit satisfies an ordinance’s requirements for consistency with a neighborhood.

A ministerial duty is one that leaves no room for a decision by the official. It sounds like Texas law requires officials to issue notices. As such, they have no discretion to decide whether or not to issue the notices.

The typical remedy for an official’s failure to perform a ministerial duty is traditional mandamus. That’s a request to the court to compel officials to perform their duties. I’m this case, issue the required notices.

Often, an official will argue that the duty is discretionary. If so, the remedy becomes administrative mandamus, where an injured party must prove that the official acted without jurisdiction or in excess of the official’s discretion. Given the ruling that the Texas officials were not acting ultra vires, it sounds as though their duty to issue notices is ministerial.

Good luck with the outcome. Even if mandamus is barred by collateral estoppel or res judicata for these structures, it will be available for other signs in the future.

Typo in my reply. “I’m this case” in the last sentence of the third paragraph should be “In this case.”. Thanks.

Without knowing TXDOT’s side of the story, it appears to be another case of Government officials lacking common sense and fairness. This is why many wish for limited government bureaucracy.

Interesting article for sure. Good job!