by Kerry Yoakum, Vice President of Government Affairs, OAAA.

by Kerry Yoakum, Vice President of Government Affairs, OAAA.

(Kerry Yoakum, an attorney at OAAA, takes a look at Scenic America’s lawsuit against digital billboards from a unique perspective: as a former state regulator. Yoakum recalls the introduction of digital technology into the marketplace and what led up to the federal Guidance issued to States, 10 years ago)

Scenic America’s legal attack against digital billboards failed at every level: in federal court and on appeal. On October 16, 2017, the US Supreme Court declined to take the case.

The focal point for this long-running court fight was federal Guidance issued to the States 10 years ago. The Guidance said, “Proposed laws, regulations, and procedures that would allow permitting CEVMS (changeable electronic variable message signs) . . . do not violate a prohibition against ‘intermittent’ or ‘flashing’ or ‘moving’ lights as those terms are used in the various FSAs (Federal State Agreements) that have been entered into during the 1960s and 1970s.”

The 2007 Guidance also suggested operational best practices such as duration of message, transition time, spacing, brightness, and location.

For the sake of context, let’s recall what led up to this federal Guidance in 2007 that said states could allow and regulate digital billboards.

I offer a unique perspective as a former state regulator. In my opinion, the industry was a step ahead.

As digital technology migrated to billboards, the industry:

- Pioneered research on traffic safety

- Set standards

- Partnered with government on behalf of public safety

- Showed that digital billboards are recyclable and achieved big gains in energy efficiency, while also enhancing commercial property values.

History

My first exposure to digital billboards occurred when I was a regulator with the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT).

A precursor technology to digital change of copy was known as tri-vision, changeable messages on motorized slats. In 1996, FHWA issued a memo that said, “Changeable message signs are acceptable for off-premise signs, regardless of the type of technology used . . .if such interpretation was consistent with State law,” with no flashing, intermittent, or moving lights. (Barbara Orski, FHWA Director of Real Estate Services, July 17, 1996).

Ohio and some other states took steps to approve off-premise electronic billboards after reviewing state law in light of FHWA’s 1996 memo.

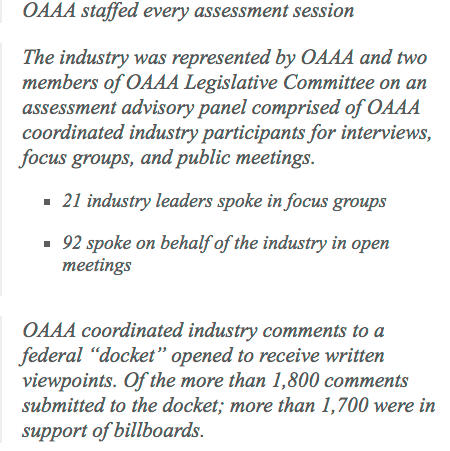

In 2006, FHWA asked outside consultants to examine billboard controls. The consultants collected input from regulators, the industry, and billboard critics via 100+ interviews, multiple focus groups, and seven field hearings. OAAA coordinated the industry’s voice.

A report for FHWA dated November 21, 2006, said divergent stakeholders perceived technology as important and there was potential for agreement. This report, produced by independent conflict-resolution experts called The Osprey Group, identified “new technology standards” as the number one issue in outdoor advertising.

A report for FHWA dated November 21, 2006, said divergent stakeholders perceived technology as important and there was potential for agreement. This report, produced by independent conflict-resolution experts called The Osprey Group, identified “new technology standards” as the number one issue in outdoor advertising.

On September 25, 2007, FHWA issued a Guidance memo, updating its 1996 memo.

Traffic safety

In 2006, the federal safety agency (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) published a standard that was widely disseminated and well understood: if drivers diverted attention for more than two seconds, accident risks increase significantly. This research was conducted by experts at Virginia Tech’s Transportation Institute.

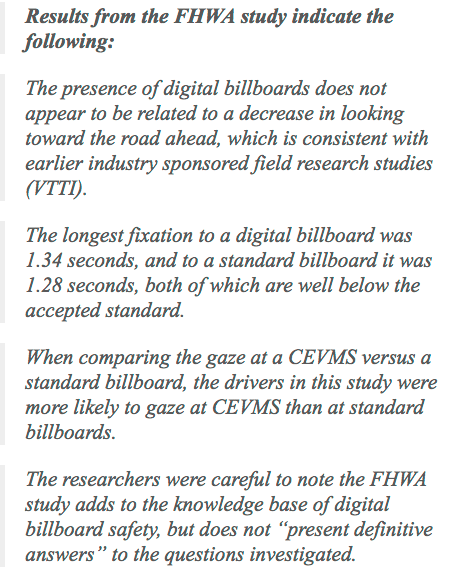

The OAAA hired Virginia Tech to drill down on a specific question: do digital billboards distract drivers or not? In March of 2007 – six months prior to the federal Guidance memo on digital billboards – experts at Virginia Tech said digital billboards are safety neutral.

Later, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) would use the same methodology – an instrumented car to track eye movements — to test safety. The federal contractor was global engineering firm SAIC, Science Applications International Corporation. The federal study, posted December 30, 2013, said eye glances in the direction of digital billboards are well under the two-second safety threshold established in 2006.

OAAA also hired outside experts to study accident records, which showed no correlation between digital billboards and crashes. The first such report, from the Cleveland, OH, market, was published in July of 2007. Similar research based on accident records would follow from four other areas (Rochester, MN; Albuquerque, NM; Reading, PA; and Richmond, VA).

Setting Standards

Digital billboards should avoid glare, said the federal Guidance issued in 2007. To achieve that goal, the industry self-regulated and collaborated with government.

Keeping pace with technology, the OAAA updated its Code of Industry Principles in April of 2006:

We are committed to ensuring that the ambient light conditions associated with standard-size digital billboards are monitored by a light sensing device at all times and that display brightness will be appropriately adjusted as ambient light levels change.

A growing number of state and local governments have adopted the industry standard to avoid glare (0.3 foot candles above surrounding light conditions). A leading expert, Dr. Ian Lewin, former president of the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, worked with OAAA to determine this limit.

Partnerships

In 2007, the FBI began using digital billboards to help find fugitives in Philadelphia. By the next year, OAAA would enter partnerships with the FBI and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children to display AMBER Alerts.

Government at all levels, including emergency managers, uses digital billboards to communicate with the public.

Today, more than 7,300 digital billboards operate nationwide. Forty-five of the 46 states with billboards have enacted laws, regulations, or policies allowing digital billboards. The industry invested in research, took steps to self-regulate, and proactively addressed critics’ claims. In retrospect, the industry was a step ahead.

[wpforms id=”9787″]

Paid Advertisement